Where do you come from, and how has that influenced where you are now?

I come from a conservative, religious, small town in the [American] midwest, and I research conservatism, religion, and gender–but in nineteenth-century Russia. My first book was about a Russian landowning family in the 1830s where the father raised the children and the mother ran the family’s finances. Part of what it does is show the wide range of ways even “traditional” or “conservative” families have organized themselves and managed household duties.

If you teach, what do you learn from your students, and what do you hope they learn from you?

The thing that makes it possible to teach the same material or courses year after year is that the students are different every time. I’m very lucky to have students from all over the world with incredibly wide-ranging views and life experiences. They make every day interesting for me and they also help to teach each other by bringing such contrasting perspectives into the classroom. But my students also vary widely in how prepared and motivated they are for college work, and balancing that is probably the hardest part about my job. My goal for my students is that they leave my class having moved forward in their ability to identify and weigh evidence, to reason through cause, effect, and context, and to read critically and write effectively. That’s what keeps me going through the days when students blow off class or turn in crappy papers, while I make less money and work more hours every year, never coming close to paying off student loans or making up financially for 8 years of post-graduate education that left me ‘overqualified’ to do anything else. It’s worth it when even one student comes out of my class being able to do things they couldn’t do when they came in.

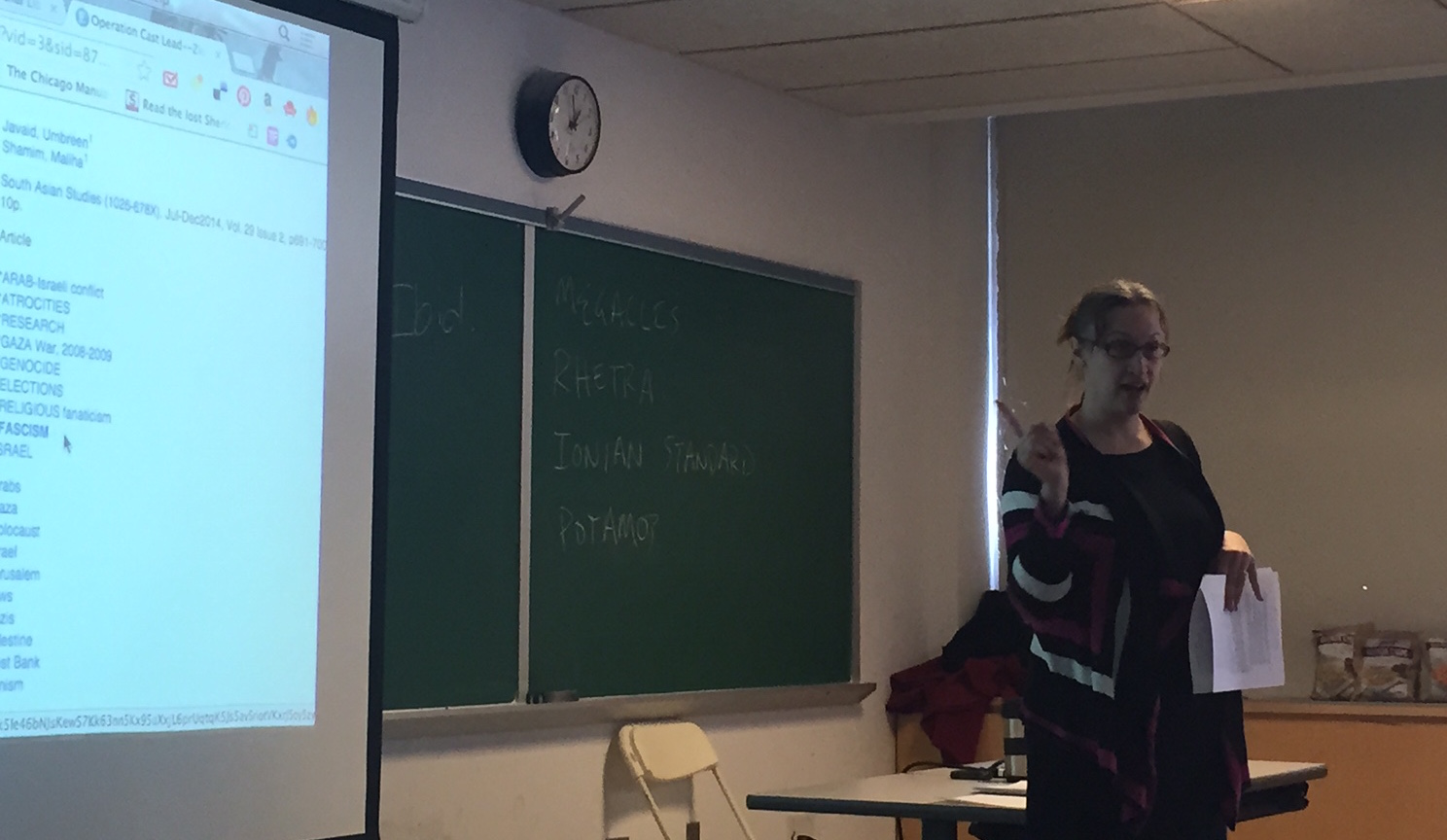

What’s your favorite thing to teach, and what kinds of things happen in your classroom?

I teach the whole range of modern European history and most enjoy teaching about the first half of the twentieth century. The period from World War I to World War II in Europe was one of the worst times in human history judging by the sheer scale of human-caused destruction. It was also a time of incredible creativity in the arts and sciences. And it was the first time that large populations actively and regularly participated in politics, with mostly terrifying results. It’s meaningful to me to teach this material because there are so many misperceptions about it in our culture. I hope that teaching the evidence from this period makes a difference in spreading a more accurate picture of what really happened. It’s also fun to teach, even though much of the material is very dark, because it deals with all the extremes of human capability and raises deep questions. Students read original documents from the period and learn to analyze them and put them in context. In my survey course on Soviet history, they do a role-playing game where they reenact a purge trial in a Soviet tank factory in the 1930s.